|

Click on the title and open the grammar:

Alfredo Trombetti, Grammatica italiana, new re-editon by Franco Luigi Viero, May 2014.

Since, for obvious reasons, this grammar can not be translated into English, we simply translate our

Prologue to this re-edition

Some time ago we ran into a catalogue of used books, in which we found the Grammatica italiana by Alfredo Trombetti, of whom we already knew the Grammatica latina, but not the Italian one, vary rare even in the public libraries and-after being ignored-now completely unknown.

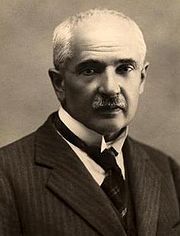

Like the Latin grammar, it is a small masterpiece. Alfredo Trombetti had planned a “Collection of manuals for teaching of classical and modern languages,” the first volume of which was precisely the aforementioned Latin grammar (1917). For each language, the editor was going to publish a grammar, a workbook and a small manual for the study of words and phrases. Between the issue of the Latin grammar and the Italian one, was released the first volume of a Course of exercises in relation to Latin grammar by A. Trombetti edited by G. Albini and E. Turazza, but we could not find it anywhere. When the Italian grammar was published, a grammar of French, one of English, Greek and Spanish too were already in preparation. But the plan got bogged down and, unfortunately, after the Italian grammar nothing else was issued. It was 1918. The Great War had come to a close. Therefore, the reasons for such a disruption is likely to be sought, on one hand, in events relating to the ownership of the Società Editrice Dante Alighieri, then belonging to Albrighi , Segati & Co., on the other, across the plots of envious colleagues and bigoted detractors. Alfredo Trombetti (1866-1929) was an unsurpassed glottologist. He became unpopular because of his theory of monogenesis of language. For understanding Trombetti's reasoning it was necessary to have a background that at the time no glottologist or linguist possessed (it was Meillet who confessed that) and nowadays no one has got. Thus, for the supercilious and obtuse Italian and foreign colleagues, there was nothing left but to resort to slander, banter and—after his sudden death—silence. Someone, poor in spirit and doctrine, still maintains that Alfredo Trombetti was not a glottologist, but a simple polyglot, almost like a circus freak. What is certain is that if 'glottologist' means a professor who badly speaks his native language, stutters somehow or other a bit of Latin and Greek, knows that there is a Sanskrit but is unable to write it in devanagārī, and avoids to converse with foreign colleagues for not having to blush with shame, then, yes, Alfredo Trombetti was not a glottologist of such species. He spoke, in fact, i.e. he had a deep knowledge of them, over eighty languages, and had learned to speak more than one hundred and twenty Italian dialects. We do not owe such information to our imagination, but to our teacher of German, when we were a lad and attended the gymnasium; he had been a pupil of Alfredo Trombetti at the University of Bologna. But back to the Italian grammar. One of the distinguishing features of this work is the frequent reference to the dialects. A barbaric custom, that contributed to the impoverishment of the Italian language heritage and after the end of World War II—even if previously spread—befell especially on the more conditionable classes of society, was to encourage parents to force their children to “talk in Italian” in contempt of dialect. This caused a forced “Italianisation” of the dialects, which were more and more contaminated, and boosted the distortion and ruin of the literary language, which till then had been the solid ground of the spoken language in schools of every degree, on the radio, at the cinema, by Civil Servants, etc. The outcome of such a process is now clearly visible and audible: the majority of State employees, journalists, high school and college students speak Italian badly and pronounce it worse still, thanks to the reforms of the various Ministers of Education as well, because of which one of the best schools in the world (until the sixties of 1900) has become an unedifying bivouac. One of the reasons, why the elementary school classes should be guided by one only native teacher, lies precisely in the dialect-territory relationship: as for the children of the first class, the teacher should explain them, playing, the differences between their dialect and spoken Italian, highlighting their own peculiarities in order to prevent unrealistic mixtures. But which teacher would be capable of fulfilling such a task? And with what schoolbook? Instead, we have recently learned that a female teacher rejected a schoolboy several times—up to encourage his parents to withdraw him from school contra legem—because he could speak only his mountain dialect. In a State where there is a compulsory school attendance, absurd indeed, it was not that child who had to be rejected, but just the teacher fired. An objection that surely many people may oppose as to the usefulness of our re-edition, is concerning the "great" strides made by linguistics. Certainly, we will not go into a barren refutation of various linguistic theories. Just a few words. From structuralism (Saussure) to transformational-generative linguistics, i.e. the so-called Chomsky revolution with its tendencies mathematicizing, there is not a single statement that a linguistic, i.e. symbolic, reasoning cannot easily refute. However, in comparison with the terminology used by Trombetti, new terms have become popular even among the philologists: for example, phoneme, morpheme, lexeme, semanteme, etc., all dreadful words invented by the structuralists. Someone said that the term 'phoneme' (which in linguistics is an expression of import, even if in Greek there is φώνημα, a Sophocles' voice meaning a sound uttered), although synonymous with 'sound', expresses more accurately the psycho-motor (!?) image of the sound, so that the 'n' of 'quando' and the 'n' of 'anche', even if they sound slightly different, would be felt by Italian speaking people psychically equivalent and, therefore, constitute a single 'phoneme'. The logical fragility of such an explanation does not need too many words. In fact, it would be necessary to show whether Italian speakers feel "psychically" those two 'n' as one only 'phoneme'. But what does "psychically" mean? Consciously? Internally? Spiritually? Well, stating that speakers of whatever language have the conscience, the inner and/or spiritual awareness of the sounds they utter, seems laughable indeed. If, instead, "psychically" means 'spiritually' 'in an abstract way' 'far from senses', the statement becomes absurd. If, lastly, feeling "psychically" means an unconscious feeling, how can a speaker 'feel', moreover unconsciously, that those two 'n' are just a sound or two? Actually, if you address the attention of gifted speaker (do not forget that the spoken language is a set-to-music language, and not everyone is able to distinguish all sound details, as not all people can feel the difference between a major tonality and a minor one), he will hear immediately that those two 'n' are different and, consequently, the corresponding graphic symbol is a rough projection, as is the rest of every written alphabet with respect to the uttered sounds. Therefore, there is not any phoneme corresponding to a sign, because any sign of any alphabet includes innumerable sounds. The inanity of modern linguistics, when it is forced—let aside acrobatic theories—to put the feet on the ground, is in the following: it works with the graphic signs, which are only a symbolic transposition not only inadequate but over all different, since signs mainly involve space and sight, while sounds mainly involve time and hearing. And languages are sounds, not alphabets. Is there a treatise of linguistics with sound recordings enclosed? So, the students, instead of learning a language, are paralysed by a mass of tangled statements—with an always meticulously up-to-date bibliography, of course! —and lose sight of their aim. Then, they graduate, and their title gives them the right to flaunt a false knowledge and to teach what they do not know. Every individual who lives in a social context must be able to communicate his thoughts in a shared manner, not only speaking but also in writing. So, every citizen must reflect on his own language structures, and every school at any rate should aim to stimulate such a reflection, because all deeds regulating public life are in writing; deeds, where distorted, unclear, contradictory and ambivalent expressions are so frequent, that a citizen is prevented from asserting his rights.

Through the re-edition of the Grammatica italina by Alfredo Trombetti we want to contribute, within our limits, to stimulate such a reflection. His author wrote it for school, for those who want to understand and learn, not for those who want to teach what they do not know. You will find a wide and faithful description of our language, exposed in a fascinating way and, above all, clear, without the useless and dusty junk, which generally stuffs and infests grammars. Finally, compared to the original edition, this re-edition has been reassembled thinking that the Internet reader will print it on A4 paper. The original text was not modified in any way. The symbol § has been added to the paragraphs' numbers. Contrary to our preferences, we did not change grave accent into acute one in words like perchè, poichè, etc. (cf. § 17). The quotations of Dante and a few others have been integrated in square brackets. The abbreviation "cfr." was changed to "cf.". In some rare cases we added a note. [All rights reserved © Franco Luigi

Viero]