Then, we are forced to examine carefully the objections of Anatole Leikin who solely picks on Charles Rosen. To tell the truth—as Leikin himself annotates without any comment—, Edward T. Cone had already noticed the problem in an interesting article in 1972: “… I have tried—he writes—to defend the repetition of the exposition of the first movement in Chopin's Sonata in B♭ minor,[2] but I now admit that I was wrong and declare that the repeat signs, as they stand, result in nonsense. Yet I am aware of no edition that offers any alternative—the most probable one being the inclusion of the opening Grave introduction in the repeated section”.[3] It is clear that Cone, who gave a proof of both great acumen and musician ear, did not know Chopin's first editions.

But, let us come back to Rosen, who in 1990 dealt with the question again, and follow Leikin's argumentations.

The harmonic matter.

Charles Rosen considers the repeat sign at the beginning of bar 5 a “faulty indication musically impossible”,[4] because the transition from the chord of bars 103-104 to bar 5 gives rise to a perfunctory deceptive cadence. This is essentially the argument of Rosen, on which depends every other consideration of more or less aesthetic character.

It is a proper remark and extremely relevant, since that passage disturbs the ear. Leikin, however, asks: “Why does V

7–vi in D-flat major sound more perfunctory than V

7–I? Rosen does not explain why a deceptive cadence is more perfunctory than a full cadence».

[5] Leikin's sarcasm is definitely out of place. In fact, it is not whether the resolution of a dominant seventh on the sixth (deceptive cadence) is more or less sloppy than the one on the tonic, but to clarify what degree is the B-flat, with which the bar 5 begins: is it a tonic,

i.e. a first degree, or a sixth one?

If the chord of dominant seventh of bar 104 resolves on the first degree, this may only be D-flat (bar 1) and not B-flat. If, instead, the same chord resolves on the sixth—as Leikin wants—this B-flat may not be at the same time both the sixth of D-flat major and the tonic of B-flat minor (bar 5). It is an overlapping "musically impossible", just like Rosen says, and Leikin does not explain how such a thing may be possible.

There is not any dispute on the modulation from the exposition to the development. Niecks praised it, but he did not mention the passage to bar 5, since probably he read the Sonata on a French or English edition.

[6] According to Leikin, therefore, in the space of an exposition Chopin would have written a clumsy modulation and a noteworthy one! Perhaps the ear of Leikin is more tuned in on the “historical context”, his… However, in order to support his argument, Leikin would have due, firstly, to bring an example of a Chopin's passage like that, that is to say a passage where a dominant seventh resolves through a deceptive cadence on a sixth, which is simultaneously a tonic. Find it, please! Chopin would never have written such a vulgarity, and actually he did not write it!

External citations.

Rosen, unfortunately, in support of his thesis gives an unhappy example, that is Weber's Sonata, Op. 24. Leikin seems to enjoy taking apart the validity of the sample.

However, as it is inane to cite Weber in order to propose an example of introduction comprised in the repeated section, the many references to demolish it only affect Rosen, and do not solve the problem of repeat sign placed by Breitkopf's proof-reader. We will omit, therefore, all the examples drawn from the musical literature of the time, because they cannot have any probative value.

For a musician with a good ear for music, the matter should end here, but not all musicians or would-be ones, have a good ear. Hence, the scrupulous musician, having detected the harmonic difficulty he cannot allocate to Chopin, asks help to a competent philologist and expert of Chopin: “That passage is unpleasant: could you check whether or not the philological analysis might comfort my ear?”

Documentation.

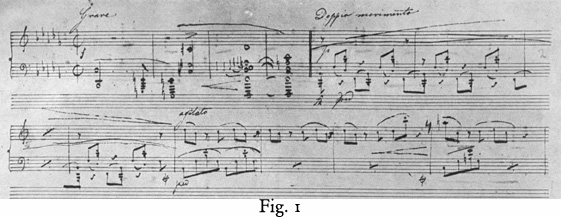

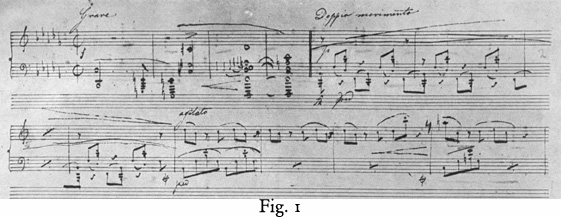

The manuscript of Chopin has gone lost; but we have a written up copy, so it seems, by Gutmann, a Chopin's pupil, for publisher Breitkopf (Fig. 1). And it is this copy that has created the problem, since the bars 4 and 5 are separated not by a simple bar-line, but by a double one (Fig. 1a). Well then, since in the first French edition, which it based on Chopin's manuscript, those two bars are separated from a simple line, a question rises spontaneous: was actual Gutmann (if was he) to add a second bar-line or was an unscrupulous and presumptuous Breitkopf's proof-reader? Perhaps a thorough examination of the inks, with the powerful tools available today, might hold a surprise. However, we believe that it is not necessary.

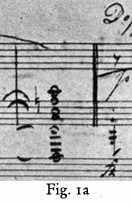

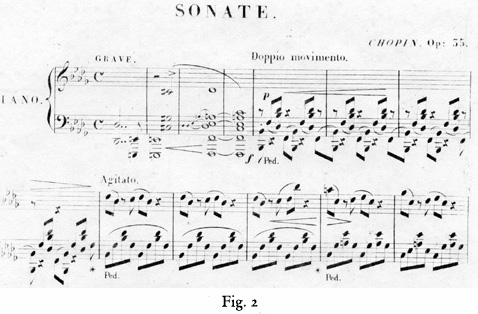

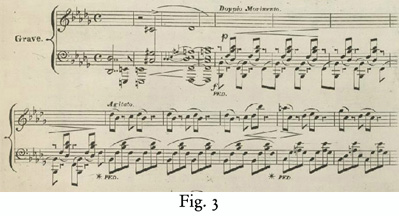

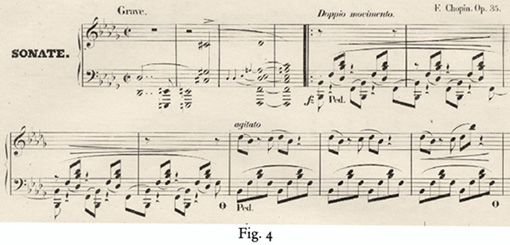

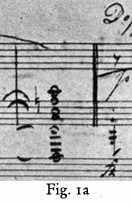

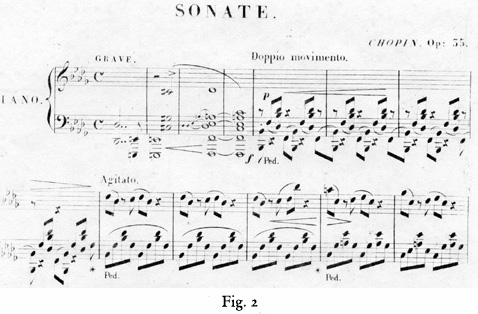

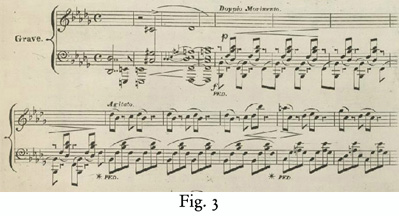

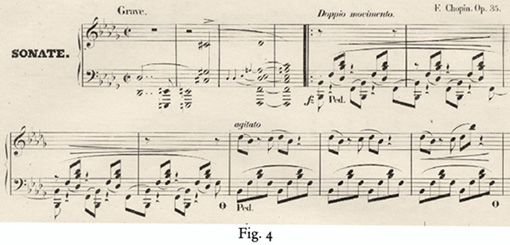

But let us see the appearance of the first three editions. Figs. 2, 3 and 4 show the first two systems respectively of the French (by Troupenas), English (by Wessel) and German (by Breitkopf) first edition.

From the splendid

Annotated Catalogue of Chopin's First Editions by Christophe Grabowski & John Rinck, Cambridge (Cambridge University Press) 2010, p. 288f.—a work, incidentally said, we will not praise enough—we find that two reprints with corrections followed Troupenas' first edition: you may find an exemplar of the first reprint in Jane Stirling's collection; an exemplar of the second one is among the so-called

partitions Dubois.

[7]We begin by noting that the line between the bars 4 and 5 is like the others; secondly, the engraver of Troupenas was not reading a copy of the manuscript of Chopin, but the autograph itself. The verbal markings, taken into consideration the graphical preferences of the three publishers, are properly put down. The reader may compare by himself the differences, which are not discussed in this article.

The repeat signs in Chopin.

But Leikin's thesis is much more sly. Since he is not a philologist, he does not want absolutely to face the question from a philological point of view; hence, he appeals to (his) “historical context” in order to demonstrate that in French and English editions the repeat signs are missing, because they were not necessary: "The entire debate about the 'correct' and the 'incorrect' first editions is simply irrelevant. A survey of early editions reveals that there was no unified practice among the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century publishers concerning the repeat sign after a slow introduction to a sonata-allegro."

[8] In other words, Leikin

a priori rejects the examination of the available documents in the light of their own context and prefers to look for a foreign context, a thousand miles away from Chopin and his publishers. Why? Because of a preconception. Leikin is personally and groundlessly convinced that the repeated section begins with the bar 5. So, he cites a series of examples drawn from works of Dussek and Hummel, where the repeat signs in fact are not necessary, even better—we add—they would be almost absurd. That is why they have been left out!

There is the rub! Before quoting unrelated examples, Leikin, through an attentive collation of autographs and first editions, would have had to show in which works Chopin's publishers—particularly Troupenas—had intentionally omitted the autograph repeat signs by common editorial practice. And we do not allude, obviously, to copying errors, but to actual forcing like that operated by Breitkopf. Secondly, through "a survey of early editions" he should have been giving detailed account of Troupenas and Wessel's editorial practice in relation to the repeat signs. Only after that, he could indulge in citing all sorts of examples.

Now, even if Leikin does not care, we want to establish whether Chopin wrote the repeat sign at the beginning of bar 5, or not. Chopin always marked the repeat signs with great care, and whoever says the contrary, has the duty to prove it. From the first manuscript until the last one, Chopin always used—with slight modifications due to the normal evolution of the handwriting—the same repeat signs, and distinguished them graphically, that is those starting the section to repeat from the ones indicating the end. These signs are very clear, unequivocal and unambiguous, such that even the most absent-minded engraver could not have ignored.

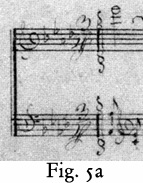

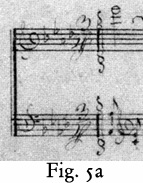

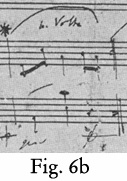

Here are some examples: in Figs. 5a and 5b, extracted from the first known Chopin's autograph,

i.e. the Polonaise in A-flat dedicated to

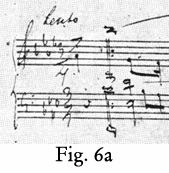

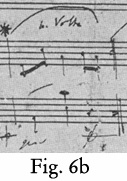

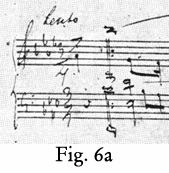

Żywny, we see both the repeat signs. We find the same signs in Figs. 6a e 6b, extracted from a lost autograph of Mazurka Op. 24, No. 3.

The

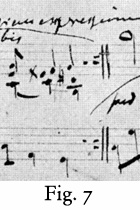

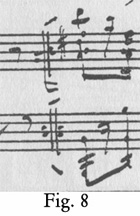

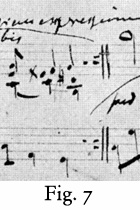

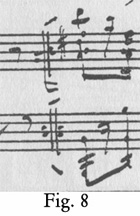

Lento con gran espressione has only the signs indicating the end of the repeated introduction (Fig. 7). In an autograph of Polonaise Op. 40, No. 1, the clear dots on both sides of the double bar-line mean that both the first eight bars and the following eight ones have to be repeated (Fig. 8).

A reader might wonder if Chopin has ever omitted to indicate the beginning repeat sign. Yes, he has, whereas it was absolutely unnecessary, as at the beginning of Sonata Op. 58: the bar 91=[1a volta] makes clear that the wide introduction has to be repeated from the beginning! And what did the first editions print? They simply copied the manuscript, as usual.

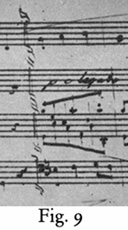

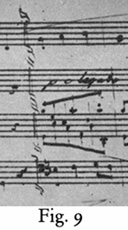

About the repetition of the introductions should be noted that even the exposition of first movement in Sonata Op. 4, whose introduction consists of 16 bars, must be repeated together with the whole introduction, like also the one in Sonata Op. 65. Indeed, some readers will perhaps be interested to a particular case: in one of the first manuscripts of the Trio Op. 8 (where the “Allegro” has to be repeated from the first bar), between the bar 4 and 5 of the “Scherzo” there are clear repeat signs (Fig. 9), which disappeared in the first editions.

Most probably Chopin changed his mind and included the introduction in the repeated section.

Well, if we applied Leikin's “historical context”, we shlould neglect the first editions and assert—on the ground of examples from wherever you want—the repeat signs are missing because unnecessary. Nevertheless, Leikin could rightly argue that in this case there is not any Sonata's “Allegro”, but only a Trio's “Scherzo”!

The collation of the autograph at our disposal with the first editions shows ad abundantiam that the engravers slavishly followed the writing of Chopin, except of some real graphic conventions—we allude above all to Wessel (cf. grace notes, fingering, etc.)—, which however are so obvious and constant that they do not constitute any obstacle or problem. Needless to say, blindly following the manuscript does not mean not making mistakes, because the classic mistakes of the copyist, well known in philology, are all heavily represented in all three first editions.

So, we can be confident that in the autograph of the Sonata Op. 35 there was not any repeat sign at the beginning of bar 5.

The double bar-line in the manuscript presented to Breitkopf.

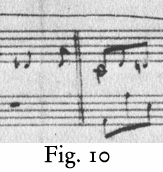

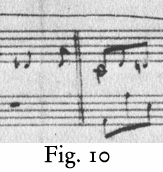

If in the autograph there was a double bar-line between bars 4 and 5, Troupenas' engraver would have copied it. The Tarantella Op. 43, printed by Troupenas as well, offers a demonstrative example to us. Fontana's copy shows between bars 3 and 4 a double bar-line (Fig. 10), but there is not any repeated section.

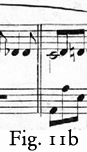

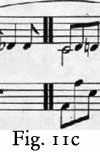

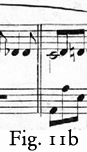

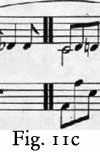

What does it mean? It means that the simple double bar-line, cited by Leikin among the evidences supporting his thesis,

[9] has no relationship with the repeat signs. Figs. 11a, 11b e 11c show how the engravers interpreted that double bar-line at the beginning of Tarantella's bar 4. In other words, supposing against the evidence that between bars 4 and 5 of the first movement of our Sonata the autograph had had a double bar-line—but the engraver of Troupenas says to us that there was not any—, this fact would not have had any relationship with the repeat signs, but it would have had the same meaning it has in the Tarantella, that is, to separate the introduction to be performed

ad libitum from the actual beginning of Tarantella's tempo.

The word expressions.

Since in French and English edition there is not any double bar-line, Leikin backs up that the repeated section is bounded by the word expressions. So, “grave”, “doppio movimento” and “agitato” from tempo and character markings change into repeat signs! Unfortunately he dos not explain how he could decode such a Chopinian cabala, after having discovered its existence!

Calling "Grave" the introduction, Chopin wants to emphasize its connection with the classical tradition. In nineteenth century the Introduction, which comes out of the “Grave” and “Intrada”, is no more an independent piece and does not assert the tonality of what it is going to introduce, because it has just got a distinctive feature, that is, it is modulating and its purpose is to create an expectation for the definitive tonality of the piece. There is no introduction, which is not modulating. Therefore, “Grave”, the name assigned by the composer to the first four bars, does not separate anything.

The expression “doppio movimento” is necessary in order to signal that from bar 5 the time changes: from

lento (“Grave”) to “

doppio movimento”, that is fast, excited (

see bar 47 of the Fantaisie Op. 49). Chopin writes it at the beginning of the exposition: where should he have put it?!

[10] The expression “agitato” (troubled, restless, rough) briefs the interpreter on the character to give to the singing voice, which is going to enter at bar 9.

In short, those three expressions do not separate anything.

In Leikin's opinion bars 5÷8 would be "an in-tempo introduction to the principal theme", because "the allegro has actually two introductions". We have to consider they are in B-flat minor, which is the definitive tonality; their configuration is fixed and does not change; there is not any expectation of the tonality no more. They may not be an introduction. Then, what are those? First of all, those bars are the beginning of the exposition, more precisely they are

warning-bars[11] addressed to the soloist. It is as if they tell him or her: "Be careful! It is your turn! Come in!". Their function is to let the soloist hear which is the tonality of the melody—which often begins on the third degree—he or she is going to sing. In arias and cabalettas of Italian operas those bars recur very frequently. Some times an only bar is enough, other times you find two bars. Both Nocturnes Op. 27 and the

Andante spianato give us a beautiful example of such a warning-bars. In our Sonata they are four to give the soloist, because of the sudden change of time, the time to get ready and to draw breath according to the need.

Troupenas' reprints.

Summing up the above: 1. We can say without fear of contradiction, that Chopin used with care the repeat signs and his publishers' engravers wrote out what they read, with some rare exception, as in the case of Breitkopf; 2. We observed that in the other Sonatas the introductions are repeated from the beginning and in one case (the "Scherzo" of the Trio) Chopin had second thoughts and incorporated the introductory bars in the repeated section; 3. The harmonic matter, which is the most important one, removes all doubt: the repeated section of the first movement in the Sonata op. 35 begins from bar 1 of “Grave”.

But that is not all.

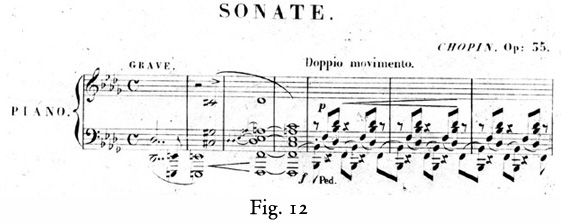

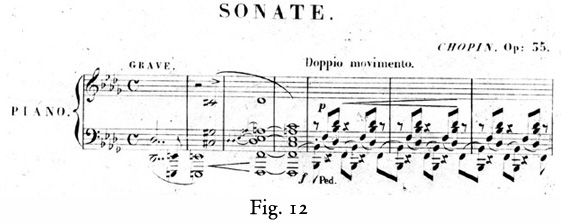

As we mentioned above, Troupenas made two reprints: Fig. 12 shows the first two systems of the second reprint. You will notice a slur has been added under the octaves of the first two bars (left hand), which Breitkopf had already printed (above them, however), because that slur was already marked in the manuscript of Gutmann.

But there is also a new little slur between F of bar 4 and B-flat of bar 5. Since such a slur indicates how to pass from “Grave” to “Doppio movimento”, it certifies that the repeated section begins from bar 1: in fact, that little slur suggests that the interpreter, mentally, has to imagine to reach the "staccato"-B-flat through a chromatic scale crescendo and accelerando. Well, imaging such an effect from bar 104 is impossible.

Moreover, Breitkopf's edition omits “p”, which is very clear in Gutmann's manuscript. Since the insertion of the repeat sign called for the proof-reader's attention, we do not believe a careless slip, but a dull presumption: most likely he found the dynamic indications “fz” and “p” contradictory.

Hofmann, Mikuli, Pugno and Mathias.

Leikin, almost satisfied and radiant with joy, finishes his article by quoting a performance of Josef Hofmann, Mikuli's edition, the one of Raoul Pugno, and Georges Mathias, who was both Pugno's teacher and a Chopin's pupil.

Let us start with what Arthur Rubinstein wrote about Hofmann: "Hofmann… was a man considered by prewar Russia and by the United States to be a giant, the heir of Anton Rubinstein. I had known him since my young years when he disillusioned me with his admitted indifference to music. With his famous gifts for mechanical matters, his main interest in the piano lay in possible changes in its construction, in the height of the keys, in different dispositions of the strings and of the acoustic holes in the frame. His magnificent grasp of the keyboard must have been inborn. Even in his playing of the masters, his chief interest lay in dynamics, in a slowly prepared crescendo ending in a volcanic outburst at the climax, and he felt great satisfaction in frightening the audience by using the violent contrast of a pianissimo followed by a sudden fortissimo smash. He had another irritating habit: He liked to bring out accompanying voices which you never heard in the performances of others. And yet, he was a pianist of great stature because, in spite of all I have said, a musical personality emerged at every concert which I cannot lightly dismiss".

[12] Perhaps, can a pianist “with admitted indifference to music” be interested to repeat signs? Josef Hofmann was a Lisztian pianist, benefited by Mother Nature. As always, Rubinstein hits the nail on the head and accurately portrays Hofmann's ways, which you can hear in every performance. Hofmann does not interpret the composer's musical thought, but the piano technique of the latter: he does not interpret Chopin, Liszt, Beethoven etc., but he forces Chopin, Liszt, Beethoven etc. to interpret Hofmann. However, it was a great pianist, with a splendid technique and a nice touch, a pianist surprising, yet always the same, the polar opposite of the Chopin's piano playing. If the citation of Hofmann's recording of Sonata Op. 35 tests anything, it can only be embarrassing for Leikin.

And now Mikuli. Mikuli's edition is a work in many ways remarkable, whose greatest contribution, the fingering, is ignored, because the chopinologists, who are pianists, cannot recognise the Chopin's fingering.

[13] His edition should be consulted with caution, because the liberties he takes, even if in good faith, are a lot. A note between bars 46 and 47 of the “Presto”

[14] confirms that Mikuli did not study the Sonata with the master: he sometimes played only the "Funeral March".

[15] The repeat sign in his edition only shows his preference for the publisher Breitkopf, whom he trusted most. He looked up the French edition too, but, without a manuscript in his hands, he did not dare to think of an abuse of the German publisher, but of a second thought of the Composer!

And what about Pugno's edition? Very rarely the testimonies of the pupils of a same teacher, whoever he may be, agree: everyone remembers different things—often distorted by personal beliefs—, because their individual relationships were different; they should be dealt with method. Let alone those of the pupils' pupils! Klindworth also says that his own edition is the “seule édition authentique”. But what value can have these statements? None!

As for Raoul Pugno,

[16] he was, yes, a pupil of Georges Mathias, but what had been Mathias? Georges Mathias “was for years the assiduous and docile student of Kalkbrenner”;

[17] after which his father had him studying with Chopin,

[18] whose teaching Georges enjoyed for many years. “The execution of Mathias is distinguished by impeccable cleanliness, a beautiful and powerful sound. Under his nimble and safe fingers, the most daring passages retain their transparent clarity. You never feel strain; you never sense a difficulty has been won. The expression, contained within the laws of style and taste, is never exaggerated. In his piano-playing you can recognize the dual parentage of the two great artists from whom he comes; nevertheless, while following the path traced by them, our eminent colleague retains his individuality, and through the experience he could modify the delicate points, which often much less inspired pupils interpreted in opposite way both by forcing the expressiveness and by granting all to the pure technique”.

[19] “Mathias—Marmontel comments—has been never keen… on public performances. The ovations, the deafening applauses rarely have tempted his ambition as an artist. He always has preferred the consent of a choice audience to the echoing with

bravos by sacrificing to the bad taste of a trivial audience”.

[20]

In the language of Marmontel, who is talking about a living colleague and therefore measures his words by an assay balance, what do those words mean? First of all, despite the years spent on studying with Kalkbrenner and Chopin, Mathias absorbed neither school. Secondly, he did not like playing piano. Why? Because he had a fixed idea for composition. We believe that Chopin knew perfectly what kind of pupil Georges Mathias was: an eternal infant prodigy. Perhaps, Chopin spoke Polish with him, since Mathias' mother was Polish. After all, a young boy with nimble fingers is better than a withered noble old lady with arthritic ones. Moreover, at a certain time Chopin stopped giving lessons to Mathias. After five, seven or eight years? We do not know because of Mathias' changeable memory. Did he finish studying with Chopin because he had learned all the secrets of Chopin's new piano school? Not at all! In fact, after Chopin's death Mathias needed to take lessons from Pleyel! It is incredible, indeed. Mathias, one of the few claimed professional pupils of Chopin, did not leave to posterity anything of any substance about the received education. An even more incredible case!

But something is still missing: Hofmann, Mikul's edition, Pugno's one, Mathias and… ? Yes, something is missing! What? Tellefsen's edition! The edition of Tellefsen precedes that of Mikuli, and Tellefsen was really one of the most important pupils of Chopin, more than Mikuli and Mathias. Why Leikin does not quote him? Perhaps because in his edition of the Sonata there is not any repeat sign at the beginning of bar 5? Yeah, that is it!

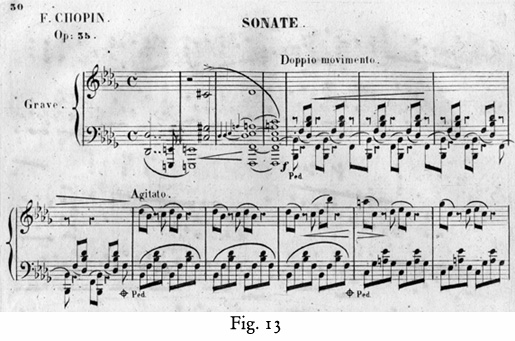

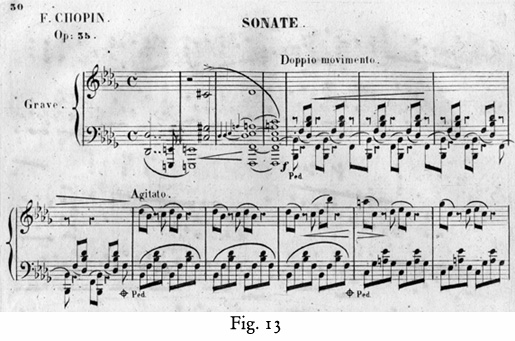

Fig. 13 reproduces the first two systems of Tellefsen's edition: there is not any repeat sign. Differently from Mikuli, Tellefsen did study the Sonata with Chopin and put in his edition corrections and variants, one of which was accepted by Mikuli too (bars 35÷37 of “Presto”). Unfortunately, Tellefsen's edition is not homogeneous.

[21] Moreover, at the time he had family troubles (his wife was fickle “qual più mal vento [like the worst wind]” rather than "qual piuma al vento" [like a feather in the wind"!), which went to the detriment of his work. Yet, where his edition does not agree with the other ones, like in Sonata Op. 35, a careful evaluation is needed, because we are faced with

variae lectiones, if not even the only text wanted by Chopin.

[22]Before concluding, a few words on the meaning and value of repetitions. When you are a student at the conservatory, you are used to avoid the repetitions, because you are inclined to consider them unnecessary and boring. In truth, the composer with the repetition offers a great opportunity to the interpreter: in plain words, to have his say. Performing the "1

a volta", the interpreter proposes what he thinks the composer wanted to express; with the repetition, i.e. the "2

a volta", however, he has a chance to comment accorgind to his own sensibility the meaning of the piece. As E. Cone wisly advises, “instead of deploring them as relics of an out-dated convention, we should welcome them as opportunities for re-examination of musical material—just as Baroque performers rejoiced in them as occasion for new ornamentation”.

[23] To abdicate a repetition is like a throw in the towel: "I have not understood, therefore I do not comment." For an interpreter is a real

débâcle! Also Glenn Gould, in his rendition of

Goldberg Variations, skips several repetitions, but it must be admitted that on the whole he succeeds in giving an appreciable equilibrium to the work. It is better skipping some variations than boring the audience with senseless notes. As for Chopin's Sonata Op. 35, if up to some time ago the pianists were allowed to abdicate the repetition of the exposition because of the bad harmonic passage (

see above), now they are not anymore. Who does not understand the meaning of repetitions, would better play pieces which do not provide any.

At last, what conclusion may we draw? That, unfortunately, we are expecting another

[24] bad and wrong edition of Chopin's Sonatas.

If publishers like to squander their money, do it, if they like! The positive aspect of the thing is that the obtuseness of some choices makes room for better ones.

However, as it is inane to cite Weber in order to propose an example of introduction comprised in the repeated section, the many references to demolish it only affect Rosen, and do not solve the problem of repeat sign placed by Breitkopf's proof-reader. We will omit, therefore, all the examples drawn from the musical literature of the time, because they cannot have any probative value.

However, as it is inane to cite Weber in order to propose an example of introduction comprised in the repeated section, the many references to demolish it only affect Rosen, and do not solve the problem of repeat sign placed by Breitkopf's proof-reader. We will omit, therefore, all the examples drawn from the musical literature of the time, because they cannot have any probative value.

The Lento con gran espressione has only the signs indicating the end of the repeated introduction (Fig. 7). In an autograph of Polonaise Op. 40, No. 1, the clear dots on both sides of the double bar-line mean that both the first eight bars and the following eight ones have to be repeated (Fig. 8).

The Lento con gran espressione has only the signs indicating the end of the repeated introduction (Fig. 7). In an autograph of Polonaise Op. 40, No. 1, the clear dots on both sides of the double bar-line mean that both the first eight bars and the following eight ones have to be repeated (Fig. 8). Most probably Chopin changed his mind and included the introduction in the repeated section.

Most probably Chopin changed his mind and included the introduction in the repeated section.

Well, if we applied Leikin's “historical context”, we shlould neglect the first editions and assert—on the ground of examples from wherever you want—the repeat signs are missing because unnecessary. Nevertheless, Leikin could rightly argue that in this case there is not any Sonata's “Allegro”, but only a Trio's “Scherzo”!

Well, if we applied Leikin's “historical context”, we shlould neglect the first editions and assert—on the ground of examples from wherever you want—the repeat signs are missing because unnecessary. Nevertheless, Leikin could rightly argue that in this case there is not any Sonata's “Allegro”, but only a Trio's “Scherzo”!

What does it mean? It means that the simple double bar-line, cited by Leikin among the evidences supporting his thesis,[9] has no relationship with the repeat signs. Figs. 11a, 11b e 11c show how the engravers interpreted that double bar-line at the beginning of Tarantella's bar 4. In other words, supposing against the evidence that between bars 4 and 5 of the first movement of our Sonata the autograph had had a double bar-line—but the engraver of Troupenas says to us that there was not any—, this fact would not have had any relationship with the repeat signs, but it would have had the same meaning it has in the Tarantella, that is, to separate the introduction to be performed ad libitum from the actual beginning of Tarantella's tempo.

What does it mean? It means that the simple double bar-line, cited by Leikin among the evidences supporting his thesis,[9] has no relationship with the repeat signs. Figs. 11a, 11b e 11c show how the engravers interpreted that double bar-line at the beginning of Tarantella's bar 4. In other words, supposing against the evidence that between bars 4 and 5 of the first movement of our Sonata the autograph had had a double bar-line—but the engraver of Troupenas says to us that there was not any—, this fact would not have had any relationship with the repeat signs, but it would have had the same meaning it has in the Tarantella, that is, to separate the introduction to be performed ad libitum from the actual beginning of Tarantella's tempo.